- Home

- Steph Bowe

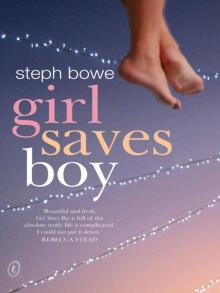

Girl Saves Boy Page 3

Girl Saves Boy Read online

Page 3

I shook my head and swallowed. ‘I can’t believe this. You killed her, you realise that? Now you suddenly want to talk?’ I spluttered.

‘You’re being ridiculous,’ Dad said. He crossed his arms and leant against the fridge.

‘I have to go to school,’ I said, leaving the room to grab my schoolbag.

‘Ignoring this won’t make it go away, Sacha!’ Dad yelled.

‘Worked pretty well for you when Mum was dying!’ I yelled back.

He didn’t kill Mum literally, but I couldn’t help but blame him.

He’d always been so distant, so lost in his own world, that he hadn’t noticed the changes in her. The changes she had made, I think, so that he would notice. The changes that went too far.

I hated myself for not seeing it coming either.

Now that I was sick again—the leukaemia back and worse than ever—he noticed. He wanted to help. I just wanted it all to end.

I wished he’d helped Mum. I wished we’d helped her.

True caught me by the sleeve of my school jumper as soon as I left homeroom, and spun me around.

I looked up at her. ‘I don’t appreciate being manhandled.’

‘It was Jewel Valentine, right?’ she said, pulling me clear of the doorway to stop me from being trampled.

‘You know what I don’t get?’ I asked. ‘Why people ask you a question when they know the answer already.’

True sighed and readjusted the clasp in her hair. ‘You drive me nuts.’

‘In an I-want-to-rip-off-your-clothes kind of way or…’

‘I went to the school registrar and guess what? Jewel Valentine’s starting school here today, and she’s in the same Art class as you.’

My eyes widened. ‘The office lady told you that? I’m surprised. Last time someone asked her to give them someone else’s timetable she read us this whole thing on the privacy act.’

‘Us?’

‘Little Al and me. He tried to get your schedule when he was fourteen. Can’t remember why, but I’m sure Al can…And I can’t help thinking you’re able to hypnotise people into giving you what you want.’ I shifted my books in my arms. Why did they have to make them so heavy? Couldn’t the people who wrote them have been more concise?

‘Everyone likes me around here.’ True shrugged. ‘Except the students. But I don’t like them either, so it doesn’t bother me.’

‘Then why so fascinated by Jewel Valentine?’ I asked. It felt strange to say her name. Like I was betraying some kind of secret between us—she had, after all, left before the ambulance arrived. I needn’t have told anybody about her. So why did I?

‘Don’t you want to meet her in a less life-threatening situation?’ True asked. So much for answering my question.

My mind said, Yes. Yes, I would. But I was afraid. I couldn’t tell True that.

I started walking down the hall towards my Geography class and True fell into step beside me.

‘Yeah, maybe, no…I don’t know. What do you think?’

‘I go and hypnotise the office lady for you, so you’d better keep going with Art—what are the alternatives, anyway? You’d lose a finger in Woodwork, and in every other subject they actually expect you to do work.’

‘Hey, I never really liked my left pinkie. It’s kind of stubby. Wouldn’t be the biggest loss.’

True shook her head. ‘I’ve got English Lit. Do me a favour and don’t go losing any body parts at least until I’ve got my university applications in. I can’t handle that kind of stress at the moment.’

‘I’ll hold off on it till next week, if it means so much to you.’

True smiled. ‘Thanks. I appreciate it.’

I was early to Art, my last class of the day, the one I always spent staring into the distance and ignoring Mr Carr.

I couldn’t draw well, but I stuck with Art because it was easy, because Mr Carr never failed anybody (he was twenty-four and yet to fall into the role of the heartless and jaded schoolteacher), and because I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life.

Mr Carr was sitting on a stool behind the teacher’s bench.

He was focused on what he was drawing, and I slunk away to the corner of the room, sat down, dropped my bag at my feet and gazed out the window at uncoordinated Year7s playing soccer on the oval.

The class wouldn’t start for a while—the only students already there, sketching and talking to one another, were the people who actually enjoyed Art, as well as those who only did their homework five minutes before class.

‘Sacha,’ said Mr Carr. ‘Do you mind if I have a word with you?’

My eyes snapped towards him. He smiled. I kept my face totally expressionless and walked over to him.

When I reached his desk, I sucked my teeth and fixed my eyes on a charcoal drawing on the wall behind him. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘How are you?’ he asked. The softness in his voice was more scary than kind. The creep.

‘I’m fine, sir.’

‘Don’t call me “sir”, please.’

‘Yes, Mr Carr.’

He sighed and tapped his fingers across the bench top. ‘What’s wrong, Sacha?’

‘Do you really think it’s worth having this conversation in class, Mr Carr?’ I asked, teeth gritted.

‘You never speak to me otherwise,’ Mr Carr said. ‘I don’t know what I’ve done to make you dislike me so much.’

I bit down hard on my bottom lip. I didn’t draw blood, but I tried to. Any excuse to leave and go to the nurse’s office.

‘I’d like you to help me understand,’ he said.

I almost laughed. ‘I’m surprised it isn’t obvious to you, Jason.’

He just sat there and stared at me, waiting.

I smiled tightly. ‘Okay then. Close your eyes… picture your happy place…’

‘Sacha, if you don’t want to talk about it now—’

‘No, I’m good. Just listen to me. I want you to imagine that your mother has recently passed away. You’re depressed, just a little cynical, and you’re doing that whole “Why me?” thing. “What did I do to deserve this?” Are you following?’

Mr Carr nodded, running his hand through his hair. His eyes flashed with something I didn’t recognise. I hoped it was terror.

‘Then,’ I laughed, ‘your dad comes home from parent-teacher evening’—I think my smile was kind of putting him off, judging by the look on his face—‘and tells you he’s met someone. Wants to talk to you about it before he goes any further. Wants you to be comfortable with it. You kick a hole in the wall, throw a lamp across the room. Remember, you’re seventeen. It’s not as if you’re a six year old having a temper tantrum. So, you’ve put an end to it. You still wonder which teacher it was, of course. Hope it wasn’t a teacher, maybe just someone he encountered at the supermarket on the way back. Almost vomit at the thought of your dad being with someone who isn’t your mum, so soon after her death.’

By this point in my spiel, the attention of the rest of the class was all on me. I could feel their stares boring into my back. I was still facing Mr Carr. He was still staring at me, wordlessly.

I laughed again. ‘Here’s the good bit. So, the following week you come home from your friend’s house a little earlier than expected—let’s call your friend “Little Al” because, well, that’s his name—and, guess what? Your dad has someone over. Not like it’s anything particularly compromising— that probably would have ended in second-degree murder. No, but it is kind of obvious that this is someone he cares about, someone who is important to him. Some smashing of objects by you ensues, a bit of screaming, a lot of swearing, some head-butting of a wall…’

Mr Carr breathed unevenly and cast his eyes down. If I’d been nice, if I’d been tactful, I could have stopped then, I could have pleaded temporary insanity to the principal.

‘And instead of your father laughing and drinking wine with your middle-aged English teacher—you’d deduced she must be the culprit who stole your dad’s heart in a fi

fteen-minute meeting and you’d vowed to drive a stake through her heart—lo and behold, it’s your Art teacher, seventeen years younger than your dad and, the cherry on top of the cake, a man.’

The clunky sliding door to the classroom opened, and everyone’s rapt attention on me was instantly diverted as Jewel Valentine stepped into the classroom.

‘Sorry I’m late,’ she muttered. I got the feeling she’d heard the last bit of my speech from outside. Her eyes—those brilliant eyes—flicked over me for only a moment, and I didn’t make out recognition.

The quiet in the classroom was unnatural.

I didn’t wait for the fallout. I grabbed my bag, swept past Jewel Valentine and didn’t stop running until I reached the corner shop.

I wasn’t always the cowardly lion. It was something that had grown in me, like a tumour. Running through my blood so thick that it had become a part of me.

Signs in shop windows along High Street:

Only one schoolchild at a time

Psychic readings—see into your future today

Apprentice pastry chef wanted—enquire within

Free eyelash tint with every full leg wax today only

We cannot guarantee that female mice are not pregnant

I walked along the streets with my hands in my pockets. There was a stillness in the air when the streetlights came on, as the last embers of the dying sun streaked through the autumn leaves, patterning raked driveways and lawns all shades of gold.

On the weekends and on school afternoons, I loved to lie in our front yard, close my eyes and feel the day’s golden rays soak into me, like I was taking it all inside me, and I was filled with this brilliant gold light.

But in the evenings, when the streetlights came on it was magical, all alone out there. I listened to the distant hum of radios, the ground reverberating with the bass of someone’s house music turned up too loud, and I could see the glow of LCD screens in people’s living rooms before the curtains were drawn for the night.

I watched the sky turn blue, indigo, black. I watched the first stars wink to life. I waited for the moon to show its face. I wandered across driveways, and I breathed in all the life going on around me.

Though mornings were painful and bitter, by evening some of my problems could be forgotten— never totally, but maybe for a few moments, like now.

It was reassuring, the people coming home, the dull white noise, the sparkle of stars that may have already died, while their light was still on its way to Earth. Listening and breathing it all in, I thought how inconsequential I was in the design. When I stood on the dotted line in the middle of the street and looked along it, all the bins lined up, tapering away perfectly into the distance like a perspective drawing…

Leaves crunched beneath my feet and I paused outside a house in a street of mown nature-strips, where the full recycle bins had already been pushed out to the curb.

The house was like the others: a faux sandstone front, an extra bedroom added as an afterthought, the kitchen facing the street.

It was my old house.

Lights on inside, people moving around. People who lived there.

I couldn’t imagine living in a house where someone had died. I don’t know whether the real estate agent ever told them, but they were better off not knowing.

I stood there on the footpath outside my old house, with the low red-brick fence at the front and the wrought-iron gate. The garden was overgrown—something neither of my parents would ever have allowed to happen—and our lavender plant was unkempt.

My mother used to pick sprigs of lavender every week—often I helped her and we’d put them in our drawers, hang them from the light fittings, put a bouquet of the sweet-smelling plant on the kitchen table.

I doubted the people who lived there now did that. I wondered who slept in my old room, the room I moved into when I was eight. I wondered whether that person admired the ceiling: the swirls of colour and joy that my dad painted for me the year we moved in.

Beside the lavender bush there was a gnome.

He wasn’t anything special—just your average garden-variety gnome: yellow hat, red shirt, blue pants. Paint a little chipped, but looking smart. Could very well go to a job interview and audition for the role of Santa’s elf. He had a nose that hinted at a drinking problem. Ceramic. Made in China.

I stared at the kitchen window. A man walked up, put something in the sink. He was looking at someone else and his eyes glittered with laughter. He turned away from the window and walked back out of sight.

I didn’t bother unlatching the gate—even as a vertically challenged person I could easily step over the fence. I walked along the path, still focused on the window. Then I looked down at the gnome, who bore an expression of outrage, and snatched him up.

As I looked back at the kitchen window, my eyes met those of the man who lived in the house where my mother died. On his face was a look of shock— or was it amusement?

I clutched my new gnome to my chest and I bolted.

Jewel

Tuesday afternoon, after Art, Mr Carr asked to see what I’d been working on.

‘This is fantastic,’ he murmured as he examined the sketch, running his finger along the lines, his head tilted. He looked pretty intense. It seemed like a normal sketch to me. A few lines in grey-lead pencil, nothing that special—it was a drawing of Geraldine, her face crinkled in a smile. I’d taken extra care etching the lines around her eyes and across her forehead. Her face was old, but her smile was young, and I hoped I’d captured her in my sketch. At least Mr Carr seemed to like it.

‘Are you sure you haven’t had any formal training?’ he asked.

‘Just school,’ I said. ‘But I’ve been drawing my whole life.’

‘Do you think…’ he murmured, ‘do you think we could put this on display? Not in the classroom…maybe out in the hall? Framed?’

‘I was actually planning on giving that to someone,’ I said. Maybe it could have been put on display? Maybe I was just being difficult, like always? But I really was planning on giving it to someone, that was no lie—I’d drawn it for Geraldine.

‘Oh,’ sighed Mr Carr. ‘I suppose that’s all right. What about your next work? Maybe that one?’

‘You think it’s all that good?’ I asked. I wasn’t fishing for compliments—no way, especially not from a teacher—I was just sceptical.

Mr Carr nodded. ‘Definitely. You should consider doing a Fine Arts degree.’

‘I wasn’t planning on going to university. I wasn’t planning on going anywhere.’

Mr Carr handed me my sketch and sat down. ‘What do you want to do after school?’

‘Maybe get an ice-cream, borrow a horror movie, curl up with a good book…’

He shook his head. ‘You know what I mean. You have to plan something, Jewel. Anything. I know I’m not the careers counsellor, but why don’t you at least apply for a couple of universities? Make up a portfolio. You’ve got the talent, and you don’t have anything to lose. If that doesn’t work out, you can fall back on your plan of not having any plans.’

‘My no-plan plan. Yeah, and become an Art teacher,’ I said.

Mr Carr’s lips twisted into a wry smile. ‘We’ll talk about this. And I’ll see if the careers counsellor can meet with you and your mother. There are so many opportunities available to you. You’d be silly not to take them up.’

‘Opportunities that you didn’t have?’ I asked.

‘Talent will open doors for you that wouldn’t be opened for other people,’ he said. ‘If you get motivated, dedicated, you can do anything. And maybe I wanted to end up an Art teacher. Maybe everyone can do what they want? Some people must want to be cleaners.’

He paused, and it seemed as if he was going to say something more, but he didn’t.

‘You’d better head off now if you want to catch the bus,’ he announced, finally. ‘Thanks for sticking around.’

‘That’s all right,’ I said. ‘Could I, uh, ask you s

omething?’

‘Fire away.’

‘You know, um, that boy you were talking to at the start of yesterday’s lesson?’

Mr Carr’s face tautened. ‘Yes.’

‘Does he skip class often?’

Mr Carr sighed. ‘I know his family from outside school. There’s some stuff going on—it isn’t your concern, Jewel.’

Normally I wouldn’t ask anything this direct— even I knew it sounded a little rude—but my curiosity got the better of me.

‘What was he speaking to you about before I arrived?’ I asked. ‘I’m pretty sure everyone in the class heard.’

He took a piece of paper from a stack of sketches and focused on it. I wasn’t sure how much time passed, but it couldn’t have been more than a few seconds, even though it felt like an hour.

My lips and throat were dry. ‘You’re right, it isn’t my business. Sorry.’

I picked up my things and made my way to the door.

‘Jewel?’ asked Mr Carr.

I spun back around, ‘Yes, sir?’

‘Promise you’ll keep on drawing?’

‘Promise.’

He smiled. The whole encounter was vaguely disconcerting.

After a brief disagreement between me and the combination lock on my locker (I’m no good at remembering series of numbers, even short ones— actually, I’m not good with numbers at all), I collected my bag and walked out of school to the bus stop to wait for the late bus with the kids from band.

A tall boy was across the road and when he looked in my direction I was too late in averting my eyes. He skip-hopped over, smiling and waving as if he knew me—I certainly didn’t know him, and two days isn’t long enough for people to start recognising you.

‘Hey, hey,’ he said. ‘Jewel!’

‘I don’t know you,’ I said, forcing a weak smile. ‘Sorry.’

I was sitting on the edge of the seat, but somehow he managed to sit down beside me and I was pushed into half a dozen trumpet players, who collapsed like dominoes. One girl grumbled at me for making her drop her instrument case.

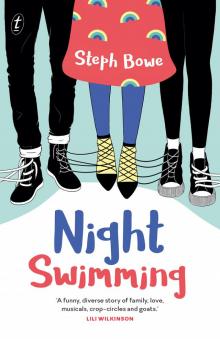

Night Swimming

Night Swimming Girl Saves Boy

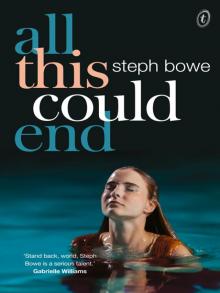

Girl Saves Boy All This Could End

All This Could End