- Home

- Steph Bowe

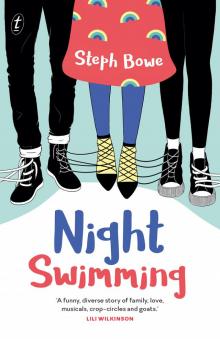

Night Swimming

Night Swimming Read online

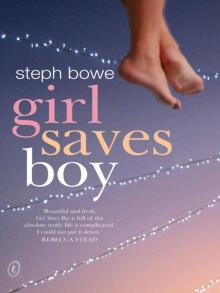

‘Beautiful and fresh, Girl Saves Boy is full of the absolute truth—life is complicated. I could not put it down.’ Rebecca Stead

‘Steph Bowe’s debut is charming and quirky and heartfelt enough to make you catch your breath when you least expect it. Readers will adore Girl Saves Boy.’ Simmone Howell

‘A charming, touching and twinkle-toed book.’ Fiona Wood

‘There’s humour and sadness, silliness and wisdom in this amazing debut.’ Readings Monthly

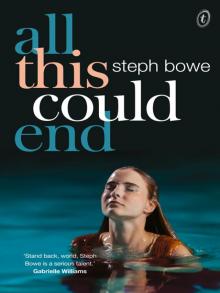

‘This book is a rare treat of gentle quiet, big-hearted sweetness and great slabs of uncomfortable truths… Even though this world keeps dealing unfair hands, the warmth of the characters and the musings about life lift this novel above the bleak to something fresh and unique.’ ABC Canberra

‘A beguiling debut novel…Bowe takes the teen romance genre and gives it an edge…A perspicacious and assured novelist.’ Australian Book Review

‘Steph Bowe’s novel is full of humour, friendship and romance, not to mention garden-gnome theft and lobster liberation. The smart sometimes snarky characters are delightfully kooky and have a lot of heart.’ Australian Books+Publishing

LONGLISTED FOR THE GOLD INKY AWARD, 2014

LONGLISTED, YOUNG ADULT NOVEL, DAVITT AWARDS FOR AUSTRALIAN WOMEN’S CRIME WRITING, 2014

‘Thoughtful with wonderful offbeat moments and quirky characters. With her distinctive blend of light-heartedness and depth, Bowe delivers a story that prompts readers to think about how far they would be willing to go for family and the value of true friendship.’ Kids’ Book Review

‘All This Could End could well be the most entertaining novel you would have read in a while.’ Magpies Magazine

‘Bowe’s characters are brimming with life and insecurities and intelligence and hope and just the perfect amount of truth and charm...Most of all, this book is just full of soul with the right dash of whimsy.’ Inkcrush

‘All This Could End is a great second novel and marks Bowe as a writer to watch.’ Viewpoint Magazine

‘Steph Bowe’s outstanding evocation of what it is like to be on the verge of adulthood demonstrates a degree of self-awareness that most writers achieve only with the benefit of hindsight.’ Junior Books+Publishing

‘Bowe elegantly captures a cast of quirky characters in this charming and believable tale.’ New Zealand Listener

Steph Bowe was born in Melbourne in 1994 and lives in Queensland. She has written two other YA novels: Girl Saves Boy and All This Could End.

stephbowe.com

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Copyright © Steph Bowe 2017

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Cover design by Jessica Horrocks

Page design by Text

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Bowe, Steph, author.

Title: Night Swimming / by Steph Bowe

ISBN: 9781925498165 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925410457 (ebook)

CONTENTS

AUTUMN

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

WINTER

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

SPRING

Twenty-Two

Acknowledgments

In loving memory of Grandpa, whose wit, inventiveness and devotion to his family will forever be cherished. You will always be our King of the Road.

And for Aunty Pat, without whom I could never have written this novel. You are a source of endless optimism and encouragement, and your presence makes all of our lives richer.

With love,

The Night Writer

My name is Kirby Arrow. I was named after the most dissenting judge in the history of the High Court of Australia. That says a lot more about my mum than it does about me.

I am seventeen. There are a lot of songs about being seventeen, but being seventeen doesn’t feel like any of them.

I have a pet goat named Stanley. He is the son of my first pet goat, Gary.

I’m training to be a carpenter. At the end of Year Ten (as far as our school goes), Mum wanted to send me away to boarding school to get my Year Twelve certificate. When I told her Mr Pool agreed to take me on as an apprentice, she sighed and said, Whatever you want to do, Kirby. I told her, If it’s good enough for Jesus, it’s good enough for me. I was half-joking but her expression stayed serious. My mum is not the talking kind, so it’s not like she launched into a tirade about making the most of my opportunities and talents. But, from the look on her face, I knew she was thinking it.

The thing is, I’m not taking up a trade because it’s the only thing I can do. I’d be fine at boarding school but I like being here with my grandfather. And Mum, too, for that matter. If I went to boarding school and then university, that would mean being away from home for at least five years. Then staying away, most likely, because there are no jobs in our town for university graduates. Mum wants me to ‘make something of myself’, because I’m smart. I don’t see why I can’t be a carpenter with quantum physics as a hobby. There’s always plenty of work if you have a trade. Really, she should be impressed that I’m subverting gender norms.

My mother runs a business manufacturing soaps made from goat’s milk. It’s a family tradition, started by my grandfather forty-something years ago. She’s expanded into other beauty products in the last few years—creams and lotions and perfumed bath bombs. She isn’t very happy doing it, so she doesn’t want me involved in the business or eventually taking it over. Which is disappointing. I think it’d be great. We could label the soaps Arrow & Daughter. I’m sure she’d prefer to leave, like my grandmother and Uncle Harry did, but she has to look after Grandad. I don’t feel the pull towards the city that everyone else seems to have; there were plenty of kids in town when I was growing up, but everyone’s vanished to boarding school. Once they’ve finished school, they stay in the city. Except for my cousin, Nathan, who did the opposite: left the city to live in the middle of nowhere with us.

We live inland, in a town called Alberton. It’s on the old highway, way down from Sydney, miles from anywhere. Since the new highway was built, the only people who come here are the ones who intend to; there are no tourists, nobody passing through. The area is prone to both droughts and floods, which means that the people who have stuck it out farming don’t exactly have the most reliable income.

We have a history of abandonment in our family. Maybe it’s in the blood. My grandmother left Grandad when Mum was only young, for reasons that I don’t really know and no one ever brings up. Long after my grandmother left and a little after I was born, my father left, too.

He left when I was a few months old, and not even Mum knows where he is and what he does. Every time I turn on the TV I think I might spot him. Not that I remember him. I’ve only seen photographs of him. He

was twenty-five when I was born, so he’d be forty-two now, and that’s plenty of life in which to accomplish things. Maybe he became a professional darts player, or a country-and-western singer, or a marine biologist. If he died, I wonder if we’d ever find out. I wonder if, somewhere, I have brothers and sisters, kids who, through the quirk of our shared genetics, have my mannerisms.

I’ve already googled, if you’re wondering. His name is Jaxon Mathieson (his parents took some creative liberties when spelling his given name), and it’s rare enough that I only had to go through a few profiles before I determined he didn’t have a Facebook account, at least not under that name.

Don’t imagine me sitting around, pondering abandonment and feeling sorry for myself. It’s just something I think about, every now and then: will my father roll into town one day in a taxi? Or a tour bus? Or a limousine? A parent you know nothing about has a lot of imaginative potential. I mean, it’s entirely possible he could be a billionaire.

Clancy Lee is my best and almost only friend, partly due to the fact that everyone else our age has left for boarding school, and partly due to the fact that we have known each other since birth, resulting in a love-from-exposure-type situation. Clancy is my exact opposite. He can’t wait to leave, but his parents want him to stay and take over their restaurant, Purple Emperor. It’s a good Chinese restaurant, but he likes musical theatre. Needless to say, no shows are put on anywhere near our town, and if he wanted to sing and act he’d have to put on a one-man show in the pub. I’m not sure it would go down well.

Clancy is also physically very different from me. He’s tall and thin and his skin agrees far more with this climate than mine does. His hair is almost always cropped short because Mrs Kingston is the only hairdresser in town and she knows what’s right—she doesn’t think the customer’s opinion matters. Clancy looks like an army cadet until his hair grows out. He is in constant motion, always performing.

Clancy’s mum’s family have lived in Australia for a few generations, while his dad moved here from Guangdong province when he was a student. Clancy had a term off school in Grade Four to visit his grandparents in Guangzhou. He is bilingual and speaks Cantonese with his parents, which I find impressive; I only speak English, and often not all that well. He can’t read or write much Chinese, though.

An Indian restaurant called Saffron Gate has opened directly across the street from Clancy’s parents’ restaurant. Fairy lights are strung along the windows, and a painted Grand Opening sign flutters in the wind.

It is 6.30 in the evening and there is no one in the restaurant.

You would expect a small town to support a new business, a new family moving in, but you forget that people deal poorly with change. Purple Emperor is full of patrons who go there for dinner every Tuesday at 6.30 p.m. and have done so since the Palaeolithic era.

Inside, a golden kitten waves at me cheerfully. Fans swirl overhead. The walls are pale pink, the carpet is beige, and the tablecloths are red with tattered gold tassels. It hasn’t changed since Clancy was born, but it’s outdated in the most charming way.

Clancy is behind the cash register. He’s peering through a pair of binoculars. His parents don’t force him to work here, but the threat of his mother’s disappointment is powerful motivation. He only rebels in inconsequential ways, like spying on the restaurant opposite when he’s supposed to be serving patrons.

‘Can confirm, daughter of the proprietor is a mega-babe, and she’s approximately our age,’ he says. ‘Or, babe at a distance.’

‘You think everyone’s a babe,’ I say. ‘You’re starved for contact with female individuals. And someone you shared baths with as a toddler automatically doesn’t count.’

Clancy gives me a pointed look. ‘Really, I spend more time with you than anybody and I am at least eighty per cent sure you’re a girl. I’m more starved for contact with male individuals.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘I have no idea. I imagine it’s Esmeralda. Like in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.’ He adopts a dreamy expression.

‘Take it from a girl: making up names for girls you don’t know is creepy. Don’t do it. Besides, isn’t that a Spanish name? They’re not serving tapas over there, Clance.’

‘Go over and say hi, please. Find out her name. Look, there she is.’ He points. She’s looking out the window. Too far away to confirm if she’s a babe or not. Not that it matters. You probably think Clancy’s a terrible objectifier but he’s really not. He’s excited about anyone even remotely the same age as us coming to town, regardless of their babe status. As am I.

‘Don’t point!’ I hiss.

‘She’s looking at us. Duck! Duck!’ The two of us crouch behind the counter.

My back to the counter, I shake my head. ‘You’re an idiot. An absolute idiot.’ Clancy’s mother is in the kitchen, chopping, and sees us through the clear plastic strips in the archway. She gives me a wave. She is used to our bizarre behaviour.

‘We should have a big showdown in the street, my family and her family,’ says Clancy, his face bathed in the glow of the drinks fridge. He puts on an old-timey Western accent. ‘This town ain’t big enough for the both of us.’ It is not a good accent. He drops out of it. ‘That sort of thing. Complete with shootout. I don’t have a revolver but I already own an Akubra, so…’

‘You’re a regular Clint Eastwood. I’m pretty sure this town is big enough for two restaurants,’ I say. When I get up from behind the counter, the girl is gone from the window opposite.

Clancy reaches for the binoculars again. I stop him. Way too creepy. He shakes his head. ‘There’s the bakery. And the newsagent sells four-day-old sandwiches. Steak or chicken parmas at the pub. It’s a lot of competition, Kirby. And now I have a rival.’

‘You’re almost definitely going to become star-crossed lovers, right?’

‘That’s what I was thinking. Romeo and Juliet, minus the dying bit. You have to go over and introduce us. Your role in the story is as…hey, does Romeo even have any female friends? You’ll have to be Mercutio. Again, minus the dying bit.’

‘Why me? If you’re the one who thinks she’s such a babe, why don’t you go over and introduce yourself?’

‘Attractive heterosexual young women exist only to be admired from a distance. They’re beautiful but dangerous if you get close. Like stray dogs, or fireworks. They’ll kill you if you get drawn in. Not including you, obviously.’

‘How do you know she’s heterosexual?’ I ask. ‘And she doesn’t look like a killer from this distance.’

‘That’s the ruse.’

‘Tone down the melodrama, would you?’

‘I can’t go over ’cause Mum’ll kill me. Gotta take orders even though everybody orders the same thing every week. The Kingstons will look at the menus for ten minutes, but they’ll still want lemon chicken and beef stir-fry, just like they’ve had every Tuesday night for the last fifteen years. Feels like Groundhog Day. This is basically child slavery. It’s the least you could do for me, Kirb.’

I sigh. ‘What do you want me to say to her?’

*

The first thing I notice about her is her hair. It’s like something out of a commercial—shiny and smooth and dark, dark brown, falling to her waist as if formed from a single sheet. When she turns her head and smiles, her hair follows, shimmering like a wave. It is otherworldly. I feel self-conscious in my ordinariness. At least my hair is up in a ponytail. When it’s out, the frizz makes me look like I’ve been electrocuted.

Her smile is not a cursory smile, like one would expect from a kid who has to waitress in her parents’ restaurant for a pitiful amount of money. No, it’s a smile that makes her eyes crinkle, that makes me feel as if she knows me, as if we are the best of friends already, as if she sees straight into my soul and understands me wholly. I am aware that this is an irrational reaction to a mere smile.

The script that Clancy and I agreed on is immediately forgotten. I was supposed to introduce myself, mentio

n Clancy, find out her name and age and the likelihood she would be our friend (also ascertaining whether there might be any possibility that she’d date Clancy) and tell her a little about our town (perhaps explaining why no one was in their restaurant, and not to take it personally). I was to say all this very coolly, nonchalantly, not betraying the fact that someone our age coming to Alberton is the most exciting thing to happen all year, apart from when an echidna walked down Main Street last month.

‘Good evening,’ she says, still smiling.

I know Clancy is going to demand a breakdown of everything about our interaction, but I already feel like keeping things to myself. She has a distinctive city accent. Living here, listening to the same voices all the time, you can hear the difference in the way someone from the city speaks. Hell, you can hear the difference in the way someone from two towns away speaks. Her accent is Australian, but not as broad as mine—in every recording I’ve ever heard of myself, I have a distinctive high-pitched whine. She doesn’t drop the last consonant, either, which I’m prone to doing. I probably only pronounce half the letters in any given word. Grandad suggested sending me away for elocution lessons, maybe a deportment course as well. He has a way of losing track of time, thinking it’s still the 1950s. Even though we’ve explained that finishing schools for young ladies are a thing of the past, he never remembers.

I do not know how long I have been standing here staring at the girl, but it’s definitely too long. I swallow.

‘Could I order a takeaway?’ I ask.

‘Certainly.’ She smiles wider. She has a gap between her two front teeth. My grandfather says that means something, something about money. Something good. Wealth, maybe.

‘I like your dress,’ I say. It’s pink—not like hot pink, more like fuchsia, halfway to purple—with intricate beadwork and a sash over one shoulder, and a cut-out at the waist.

‘Thank you.’ She glances down at herself, as if she had forgotten what she was wearing. ‘I don’t usually wear saris. It’s a special occasion. Grand opening.’ Without irony, she points to the sign out the front.

Night Swimming

Night Swimming Girl Saves Boy

Girl Saves Boy All This Could End

All This Could End